Icelandic names - everything you need to know

Find out about Iceland’s quirky naming system and discover the places that inspire some of Iceland’s most beautiful names.

September 21, 2022

Icelandic names - everything you need to know

Find out about Iceland’s quirky naming system and discover the places that inspire some of Iceland’s most beautiful names.

September 21, 2022

Iceland’s unusual naming system reflects the uniqueness of this spectacular land. An outlying island that rose out of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the wild North Atlantic, it’s a place of thrilling geology and ethereal landscapes. No wonder Icelanders have a unique character - and an unfamiliar naming system for most of us. This is a country that combines a quirky culture, weird and wonderful landscapes and a chilled, laid-back people with a droll sense of humour (think Daði Freyr of Eurovision fame). Come and visit Iceland, and see for yourself. Join Reykjavik Excursions with a whole range of exciting [tours & activities in Iceland].

Where do Icelandic names come from?

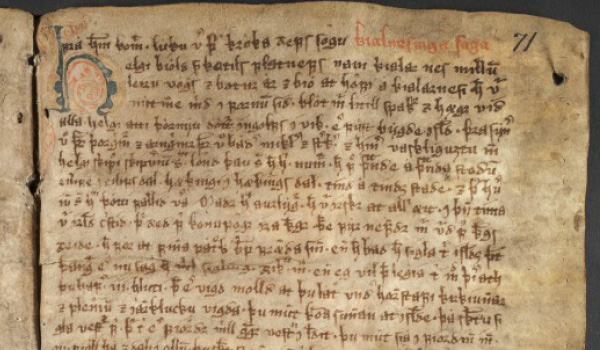

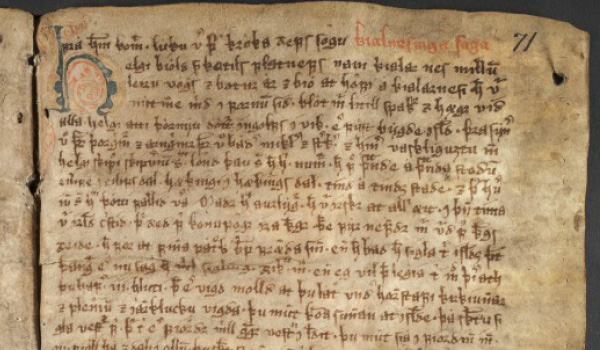

To find the answer to this question you have to head back into the mists of time. The first records of genealogical and family history, ‘The Sagas of Icelanders’ or the ‘Family Sagas’ were written in Old Icelandic, a dialect of Old Norse set down between the 9th and 11th centuries. The names that appear in those great Icelandic sagas are still used today. The most famous of all is Ingólfur Arnarson, recognised as Iceland’s first settler, his first name still given to Icelandic boys today.

The first settlers arrived primarily from Norway, then Sweden and Denmark, bringing with them their naming traditions. Based on the Germanic languages, many Icelandic names have the same roots as English German, Dutch and Scandivanian ones.Those first settlers also brought their Irish slaves with them, adding Celtic names to the mix.

Pre-Christian times, Icelandic names were Pagan. Paying homage to the great Norse deities, Icelanders would add the gods’ names as a prefix or suffix. You still find Icelandic children called after these pagan gods today: Þór - Thor, God of Thunder; Freyja, the goddess of love and fertility; Sif, Goddess of Hunt and Harvest; Óðinn, God of War and Loki, the shape-shifting God of Mischief. Traditions changed when Iceland became Christian in the Year 1,000. Common names, Kristján and Kristinn may not be as exciting as the names of the troublesome Norse gods, but they reflected Iceland’s new Christian faith.

So Icelandic names have their roots in Norse mythology, versions existing across Scandinavia, then Christianity with different forms of those Christian names existing throughout Europe. Nowadays, however, there are modern Icelandic names unique to Iceland’s discrete culture and language. They often reflect Iceland’s wild nature and dramatic landscapes.

Visit Þingvellir - Iceland’s wilderness outdoor parliament

Þingvellir or Thingvellir National Park - what a location for a parliament! Wild and inhospitable, it came into existence in response to the too-powerful Ingólfur clan - the descendents of that first settler. To create a balance of power, a general assembly - ‘the Alþingi’ - was introduced in the Year 874, according to the Book of Settlements. From around the Year 930, members of parliament met from far and wide by the River Öxará to to put down Icelandic laws, making the Alþingi the oldest parliament in the world. The outdoor assembly continued right up to 1798, Þingvellir - meaning the Assembly Plains - was for sure an inspirational landscape in which to shape the future of a country. On the Golden Circle Tour you can visit this site, not just one of historic and cultural importance, but also great geological significance. Wander along the rift valley where the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates are slowly drifting apart. Combine your trip with other geological wonders: the Geysir Geothermal Area and Gullfoss Waterfall. And while you’re at it, why not extend your trip to take in some of the other top waterfalls in Iceland?

How does Icelandic naming work?

Traditionally in Iceland, a new-born child takes the first name of their father alongside ‘son of’ or ‘dóttir (daughter) of’, depending on the child’s gender. In the past, this tradition was not unique to Iceland. The naming system was also used in Scandinavia centuries ago, as well as in Celtic cultures, but in more recent times it has been replaced with fixed surnames that are passed down from generation to generation. Uniquely, Iceland has continued with the ancient tradition of naming a child after its parent’s Christian name, the name changing with each new generation.

How does this ancient naming tradition work in modern Iceland? While the new-born is traditionally given the first name of the father alongside ‘son or daughter of’, increasingly the first name of the mother or even both parents are added. To ensure continuity of lineage, Icelanders often give their child the first name of a grandparent, a name that is handed down through the generations. Superstition plays a role too. If an expectant mother sees a relative in her dreams - particularly a deceased one - she may feel compelled to call her unborn child after that relative, fearing her child will come to harm otherwise.

But changes are afoot. Some Icelanders combine traditional naming with a family name of their own choice. In same-sex partnerships the parents may take the names of the two fathers or two mothers. Off-spring identifying as non-binary can use the suffix ‘bur’ - the neutral ‘child of’ rather than the gender-specific ‘son of’ or ‘daughter of’.

Meet the daughters and sons of Iceland

Treat yourself to a combined Golden Circle & City sightseeing - Hop on, Hop off - Tour. Meet some ‘of the sons and daughters’ of Iceland in the city and at work at the Friðheimar Cultivation Centre where fruit and vegetables are grown organically with the aid of geothermal heat. Combine these cultural experiences with some of Iceland’s awe-inspiring landmarks on the Golden Circle.

Do all Icelandic last names end in son or dóttir?

Almost always, yes. There are a few exceptions, usually for the children of incomers. In Iceland, a person is called by their first name in both formal and informal situations, or sometimes addressed using both names. As family names generally don’t exist, the last name (son and daughter of) is never used on its own. Sometimes, Icelanders adopt a middle name for clarification.

The naming tradition is about protecting Iceland’s heritage and linguistic identity with its complex grammatical rules for names. In fact, the Icelandic Naming Committee states the name should be able to have a genitive ending or have been adapted through custom in the Icelandic language. Secondly, it must be adaptable to the structure of the Icelandic language and spelling conventions. Sounds complicated? Only as complicated as the Icelandic language.

Why don’t Icelanders have family names?

Traditionally, there are no family names in Iceland. Iceland is keen to hold onto the old patronymic (increasingly matronymic) custom whereby the child is given its father’s or mother’s Christian name and is referred to as the son or daughter of. Iceland is a country that values tradition and customs and has a strong sense of family. But it also means there’s no family lineage carried down through a single surname. You would imagine Iceland’s naming system would make it difficult to trace a family tree. Not so. The Book of Icelanders - ‘Íslendingabók’ is used to trace genealogy and dates back well over a thousand years. In fact, it’s probably easier for Icelanders to trace their family tree than people from other countries. The extensive database, the relatively small population and a keen interest in family heritage - pretty much a national obsession - means the population keeps well up-to-date with their family lineage.

Iceland’s year-round charms

When is the best time to visit Iceland and meet the people of this chilled and chilly island? Simply put, there isn’t one. Come in summer for warmer temperatures. Visit later in the year for a tour of the Northern Lights - the dance of the night sky. Winter’s ice and snow cover this already magical landscape in enchanting blues, silvers and whites. Spring brings the light. Want to hike on a glacier or alongside a smouldering lava field, swim through the waters between the drifting-apart tectonic plates, soak in a hot stream or watch the aurora? Check out this guide to the best time to visit Iceland for more information.

Do all Icelandic names mean something?

Names in Iceland often have a poetic feel to them. They might even contain a story. Some Icelanders are called after colourful Norse gods. Others are named after a mountain, volcano or even a feeling. Not surprisingly, nature is central to Icelanders - geysers, hot springs, volcanoes and glaciers all make their presence felt in this land of fire and ice. Hekla and Katla, two well-known female names, are named after two of Iceland’s most notorious volcanoes. You can find out why volcanoes are an ever-present force in Iceland in this guide to Iceland’s volcanoes and how they have impacted on the island’s population over the centuries. No wonder they creep into names! As you’d imagine snow and ice also figure in Icelandic names. Jökull, meaning glacier, is a male name in Iceland. Jaki means ice-berg. Íseldur combines ice and fire to create the perfect Icelandic name. To discover why glaciers, snow and ice inspire Icelandic names check out this ultimate guide to glaciers in Iceland.

The Icelandic Naming Committee

‘What’s in a name?’ to quote Shakespeare. Well, everything, if you are Icelandic. You can’t give your child any old name in Iceland. And if you come up with a brand-new name, it has to be run past the Icelandic Naming Committee, established relatively recently in 1991. Would the Icelandic Naming Committee have accepted Bob Geldof’s Fifi Trexi-Bell or Frank Zappa’s Moon Unit, Dweezil, Diva Thin Muffin, Apple Martin and Blue Ivy? Probably not. In fact, the naming rules stipulate the name submitted for consideration should not cause the newborn future embarrassment. A thoughtful and kind gesture from the naming committee that perhaps should be extended to other countries! Hel, Ruler of the Underworld and Skessa, a female troll, are just two such proposed names that have been rejected in the past. The committee is also thorough: approved middle names, although not common in Iceland, are listed separately from first names, and they can’t be used interchangeably. The kindness continues: If the child has a parent who is not an Icelander, they are allowed to have one name that might not be on the approved list of names.

Ultimately, there are mixed feelings about the Icelandic Naming Committee. While it strives to protect Icelandic naming traditions, others argue not being able to give your child the name you want is against basic human rights.

The power of a name - the power of nature on Reykjanes Peninsula

You can see why Iceland’s landscapes play a part in Icelandic names. The power of a name - the power of nature - can be experienced on this combined tour of Volcanic Wonders & The Blue Lagoon. Visit Reykjanes Geopark, dividing two continents, the boiling mud pools of Seltún and the steaming lava fields. Experience volcanic craters, windblown palagonite and petrified troll formations. Hike up to Fagradalsfjal, Iceland’s newest volcano and walk between two continents before finishing at the Blue Lagoon. Here you’ll feel the ground beneath you move - not just because of the intense blue of the lagoon but also because of the bubbling water and boiling steam rising up from the earth.

What are the most common Icelandic Names?

Kristín and Anna, Margret and Guðrún have all been enduring choices for girls since the arrival of Christianity in Iceland and Jón and Magnús for boys . Kristin and Kristján take the prefix of Christ, Guðleifur and Guðfinna the prefix of God. But Old Norse names have also endured. The names of the Norse gods Loki, Óðinn, Sif and Þór are common names for children to this day.

Common names also reflect Iceland’s inspirational nature: the female Hrefna is shared with the minke whale. Popular names are linked to the birch trees of Iceland: Birkir, Bjarki and Björk especially. Other popular names refer to birds and flowers. Names with the prefixes Sæ- and Haf- are also common, meaning sea or ocean.

The call of the wild

Don’t limit yourself to the Golden Circle on a trip-of-a-lifetime to Iceland. Take a tour of Iceland’s wildest and most scenic corners. Check out this list of must-see places in Iceland for inspiration. Don’t miss the opportunity to go whale watching from Akureyri on the north coast. Look out for Eyjafjord humpbacks with expert whale-watching guides.

Fun facts about the Icelandic Naming System

• Icelanders don’t change their surname on marriage, making divorce less complicated.

• If you live in Iceland but are not Icelandic, you can choose from a list of given names that don’t contain those tricky alphabet letters and accents. You can’t go wrong with Ari, Hilmir and Nói for boys, or Lukka, Lind and Sunna for girls. Once again the Icelandic Naming Committee is very helpful. It makes life just that bit easier for non-Icelandic relatives too.

• Icelandic names often reflect the character of the newborn - or at least the characters the parents would like for their child. Even the thirteen Yule Lads have names that reflect their characters: Hurdaskellir is the ‘door-Slammer’, for example, or Kertasnikir, ‘the (candle) thief’.

• Chosen names should not contain letters that don’t appear in the Icelandic alphabet (with occasional exceptions).

• Some Icelandic names perfectly capture the dark beauty of Iceland’s landscapes. Take Sindri, meaning ‘gloomy’ or ‘to glow - or Sæunn meaning ‘ocean wave’ or ‘she who cares for the sea’.

Find out more fun facts about Iceland’s unique and quirky culture in this blog outlining some of Iceland’s most endearing oddities.

Ocean waves on the south shore

The north Atlantic island is in turn battered and caressed by the ocean. No wonder there are Icelandic names paying homage to the sea. You too can discover the power of Iceland's waters. Take a tour of Iceland’s South Shore, the black beach, raging surf and basalt columns at Reynisfjara. Continue on to Jökulsárlón Glacier Lagoon with its sculpted ice-bergs bobbing on Atlantic surf or scattered along the striking black Diamond Beach. The guide to Jökulsárlón Glacier Lagoon will tell you everything you need to know about this enchanting corner of Iceland.

With all its wonderful cultural and geographic idiosyncrasies, Iceland is a fascinating destination. Start planning for a unique holiday. Head over to Iceland tours from Reykjavik for inspiration.

REYKJAVIK EXCURSIONS BLOG

Get inspired! Information and tips and must see places in Iceland, fun facts, customs and more.

The Silver Circle of West Iceland - Your Guide

You’ve heard of the Golden Circle, but here’s why you should head to Iceland’s western region to explore the msytical Silver Circle tour route.

Read BlogIcelandic names - everything you need to know

Find out about Iceland’s quirky naming system and discover the places that inspire some of Iceland’s most beautiful names.

September 21, 2022

Icelandic names - everything you need to know

Find out about Iceland’s quirky naming system and discover the places that inspire some of Iceland’s most beautiful names.

September 21, 2022

Iceland’s unusual naming system reflects the uniqueness of this spectacular land. An outlying island that rose out of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the wild North Atlantic, it’s a place of thrilling geology and ethereal landscapes. No wonder Icelanders have a unique character - and an unfamiliar naming system for most of us. This is a country that combines a quirky culture, weird and wonderful landscapes and a chilled, laid-back people with a droll sense of humour (think Daði Freyr of Eurovision fame). Come and visit Iceland, and see for yourself. Join Reykjavik Excursions with a whole range of exciting [tours & activities in Iceland].

Where do Icelandic names come from?

To find the answer to this question you have to head back into the mists of time. The first records of genealogical and family history, ‘The Sagas of Icelanders’ or the ‘Family Sagas’ were written in Old Icelandic, a dialect of Old Norse set down between the 9th and 11th centuries. The names that appear in those great Icelandic sagas are still used today. The most famous of all is Ingólfur Arnarson, recognised as Iceland’s first settler, his first name still given to Icelandic boys today.

The first settlers arrived primarily from Norway, then Sweden and Denmark, bringing with them their naming traditions. Based on the Germanic languages, many Icelandic names have the same roots as English German, Dutch and Scandivanian ones.Those first settlers also brought their Irish slaves with them, adding Celtic names to the mix.

Pre-Christian times, Icelandic names were Pagan. Paying homage to the great Norse deities, Icelanders would add the gods’ names as a prefix or suffix. You still find Icelandic children called after these pagan gods today: Þór - Thor, God of Thunder; Freyja, the goddess of love and fertility; Sif, Goddess of Hunt and Harvest; Óðinn, God of War and Loki, the shape-shifting God of Mischief. Traditions changed when Iceland became Christian in the Year 1,000. Common names, Kristján and Kristinn may not be as exciting as the names of the troublesome Norse gods, but they reflected Iceland’s new Christian faith.

So Icelandic names have their roots in Norse mythology, versions existing across Scandinavia, then Christianity with different forms of those Christian names existing throughout Europe. Nowadays, however, there are modern Icelandic names unique to Iceland’s discrete culture and language. They often reflect Iceland’s wild nature and dramatic landscapes.

Visit Þingvellir - Iceland’s wilderness outdoor parliament

Þingvellir or Thingvellir National Park - what a location for a parliament! Wild and inhospitable, it came into existence in response to the too-powerful Ingólfur clan - the descendents of that first settler. To create a balance of power, a general assembly - ‘the Alþingi’ - was introduced in the Year 874, according to the Book of Settlements. From around the Year 930, members of parliament met from far and wide by the River Öxará to to put down Icelandic laws, making the Alþingi the oldest parliament in the world. The outdoor assembly continued right up to 1798, Þingvellir - meaning the Assembly Plains - was for sure an inspirational landscape in which to shape the future of a country. On the Golden Circle Tour you can visit this site, not just one of historic and cultural importance, but also great geological significance. Wander along the rift valley where the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates are slowly drifting apart. Combine your trip with other geological wonders: the Geysir Geothermal Area and Gullfoss Waterfall. And while you’re at it, why not extend your trip to take in some of the other top waterfalls in Iceland?

How does Icelandic naming work?

Traditionally in Iceland, a new-born child takes the first name of their father alongside ‘son of’ or ‘dóttir (daughter) of’, depending on the child’s gender. In the past, this tradition was not unique to Iceland. The naming system was also used in Scandinavia centuries ago, as well as in Celtic cultures, but in more recent times it has been replaced with fixed surnames that are passed down from generation to generation. Uniquely, Iceland has continued with the ancient tradition of naming a child after its parent’s Christian name, the name changing with each new generation.

How does this ancient naming tradition work in modern Iceland? While the new-born is traditionally given the first name of the father alongside ‘son or daughter of’, increasingly the first name of the mother or even both parents are added. To ensure continuity of lineage, Icelanders often give their child the first name of a grandparent, a name that is handed down through the generations. Superstition plays a role too. If an expectant mother sees a relative in her dreams - particularly a deceased one - she may feel compelled to call her unborn child after that relative, fearing her child will come to harm otherwise.

But changes are afoot. Some Icelanders combine traditional naming with a family name of their own choice. In same-sex partnerships the parents may take the names of the two fathers or two mothers. Off-spring identifying as non-binary can use the suffix ‘bur’ - the neutral ‘child of’ rather than the gender-specific ‘son of’ or ‘daughter of’.

Meet the daughters and sons of Iceland

Treat yourself to a combined Golden Circle & City sightseeing - Hop on, Hop off - Tour. Meet some ‘of the sons and daughters’ of Iceland in the city and at work at the Friðheimar Cultivation Centre where fruit and vegetables are grown organically with the aid of geothermal heat. Combine these cultural experiences with some of Iceland’s awe-inspiring landmarks on the Golden Circle.

Do all Icelandic last names end in son or dóttir?

Almost always, yes. There are a few exceptions, usually for the children of incomers. In Iceland, a person is called by their first name in both formal and informal situations, or sometimes addressed using both names. As family names generally don’t exist, the last name (son and daughter of) is never used on its own. Sometimes, Icelanders adopt a middle name for clarification.

The naming tradition is about protecting Iceland’s heritage and linguistic identity with its complex grammatical rules for names. In fact, the Icelandic Naming Committee states the name should be able to have a genitive ending or have been adapted through custom in the Icelandic language. Secondly, it must be adaptable to the structure of the Icelandic language and spelling conventions. Sounds complicated? Only as complicated as the Icelandic language.

Why don’t Icelanders have family names?

Traditionally, there are no family names in Iceland. Iceland is keen to hold onto the old patronymic (increasingly matronymic) custom whereby the child is given its father’s or mother’s Christian name and is referred to as the son or daughter of. Iceland is a country that values tradition and customs and has a strong sense of family. But it also means there’s no family lineage carried down through a single surname. You would imagine Iceland’s naming system would make it difficult to trace a family tree. Not so. The Book of Icelanders - ‘Íslendingabók’ is used to trace genealogy and dates back well over a thousand years. In fact, it’s probably easier for Icelanders to trace their family tree than people from other countries. The extensive database, the relatively small population and a keen interest in family heritage - pretty much a national obsession - means the population keeps well up-to-date with their family lineage.

Iceland’s year-round charms

When is the best time to visit Iceland and meet the people of this chilled and chilly island? Simply put, there isn’t one. Come in summer for warmer temperatures. Visit later in the year for a tour of the Northern Lights - the dance of the night sky. Winter’s ice and snow cover this already magical landscape in enchanting blues, silvers and whites. Spring brings the light. Want to hike on a glacier or alongside a smouldering lava field, swim through the waters between the drifting-apart tectonic plates, soak in a hot stream or watch the aurora? Check out this guide to the best time to visit Iceland for more information.

Do all Icelandic names mean something?

Names in Iceland often have a poetic feel to them. They might even contain a story. Some Icelanders are called after colourful Norse gods. Others are named after a mountain, volcano or even a feeling. Not surprisingly, nature is central to Icelanders - geysers, hot springs, volcanoes and glaciers all make their presence felt in this land of fire and ice. Hekla and Katla, two well-known female names, are named after two of Iceland’s most notorious volcanoes. You can find out why volcanoes are an ever-present force in Iceland in this guide to Iceland’s volcanoes and how they have impacted on the island’s population over the centuries. No wonder they creep into names! As you’d imagine snow and ice also figure in Icelandic names. Jökull, meaning glacier, is a male name in Iceland. Jaki means ice-berg. Íseldur combines ice and fire to create the perfect Icelandic name. To discover why glaciers, snow and ice inspire Icelandic names check out this ultimate guide to glaciers in Iceland.

The Icelandic Naming Committee

‘What’s in a name?’ to quote Shakespeare. Well, everything, if you are Icelandic. You can’t give your child any old name in Iceland. And if you come up with a brand-new name, it has to be run past the Icelandic Naming Committee, established relatively recently in 1991. Would the Icelandic Naming Committee have accepted Bob Geldof’s Fifi Trexi-Bell or Frank Zappa’s Moon Unit, Dweezil, Diva Thin Muffin, Apple Martin and Blue Ivy? Probably not. In fact, the naming rules stipulate the name submitted for consideration should not cause the newborn future embarrassment. A thoughtful and kind gesture from the naming committee that perhaps should be extended to other countries! Hel, Ruler of the Underworld and Skessa, a female troll, are just two such proposed names that have been rejected in the past. The committee is also thorough: approved middle names, although not common in Iceland, are listed separately from first names, and they can’t be used interchangeably. The kindness continues: If the child has a parent who is not an Icelander, they are allowed to have one name that might not be on the approved list of names.

Ultimately, there are mixed feelings about the Icelandic Naming Committee. While it strives to protect Icelandic naming traditions, others argue not being able to give your child the name you want is against basic human rights.

The power of a name - the power of nature on Reykjanes Peninsula

You can see why Iceland’s landscapes play a part in Icelandic names. The power of a name - the power of nature - can be experienced on this combined tour of Volcanic Wonders & The Blue Lagoon. Visit Reykjanes Geopark, dividing two continents, the boiling mud pools of Seltún and the steaming lava fields. Experience volcanic craters, windblown palagonite and petrified troll formations. Hike up to Fagradalsfjal, Iceland’s newest volcano and walk between two continents before finishing at the Blue Lagoon. Here you’ll feel the ground beneath you move - not just because of the intense blue of the lagoon but also because of the bubbling water and boiling steam rising up from the earth.

What are the most common Icelandic Names?

Kristín and Anna, Margret and Guðrún have all been enduring choices for girls since the arrival of Christianity in Iceland and Jón and Magnús for boys . Kristin and Kristján take the prefix of Christ, Guðleifur and Guðfinna the prefix of God. But Old Norse names have also endured. The names of the Norse gods Loki, Óðinn, Sif and Þór are common names for children to this day.

Common names also reflect Iceland’s inspirational nature: the female Hrefna is shared with the minke whale. Popular names are linked to the birch trees of Iceland: Birkir, Bjarki and Björk especially. Other popular names refer to birds and flowers. Names with the prefixes Sæ- and Haf- are also common, meaning sea or ocean.

The call of the wild

Don’t limit yourself to the Golden Circle on a trip-of-a-lifetime to Iceland. Take a tour of Iceland’s wildest and most scenic corners. Check out this list of must-see places in Iceland for inspiration. Don’t miss the opportunity to go whale watching from Akureyri on the north coast. Look out for Eyjafjord humpbacks with expert whale-watching guides.

Fun facts about the Icelandic Naming System

• Icelanders don’t change their surname on marriage, making divorce less complicated.

• If you live in Iceland but are not Icelandic, you can choose from a list of given names that don’t contain those tricky alphabet letters and accents. You can’t go wrong with Ari, Hilmir and Nói for boys, or Lukka, Lind and Sunna for girls. Once again the Icelandic Naming Committee is very helpful. It makes life just that bit easier for non-Icelandic relatives too.

• Icelandic names often reflect the character of the newborn - or at least the characters the parents would like for their child. Even the thirteen Yule Lads have names that reflect their characters: Hurdaskellir is the ‘door-Slammer’, for example, or Kertasnikir, ‘the (candle) thief’.

• Chosen names should not contain letters that don’t appear in the Icelandic alphabet (with occasional exceptions).

• Some Icelandic names perfectly capture the dark beauty of Iceland’s landscapes. Take Sindri, meaning ‘gloomy’ or ‘to glow - or Sæunn meaning ‘ocean wave’ or ‘she who cares for the sea’.

Find out more fun facts about Iceland’s unique and quirky culture in this blog outlining some of Iceland’s most endearing oddities.

Ocean waves on the south shore

The north Atlantic island is in turn battered and caressed by the ocean. No wonder there are Icelandic names paying homage to the sea. You too can discover the power of Iceland's waters. Take a tour of Iceland’s South Shore, the black beach, raging surf and basalt columns at Reynisfjara. Continue on to Jökulsárlón Glacier Lagoon with its sculpted ice-bergs bobbing on Atlantic surf or scattered along the striking black Diamond Beach. The guide to Jökulsárlón Glacier Lagoon will tell you everything you need to know about this enchanting corner of Iceland.

With all its wonderful cultural and geographic idiosyncrasies, Iceland is a fascinating destination. Start planning for a unique holiday. Head over to Iceland tours from Reykjavik for inspiration.

REYKJAVIK EXCURSIONS BLOG

Get inspired! Information and tips and must see places in Iceland, fun facts, customs and more.

The Silver Circle of West Iceland - Your Guide

You’ve heard of the Golden Circle, but here’s why you should head to Iceland’s western region to explore the msytical Silver Circle tour route.

Read Blog